State as a Snapshot

State variables might look like regular JavaScript variables that you can read and write to. However, state behaves more like a snapshot. Setting it does not change the state variable you already have, but instead triggers a re-render.

You will learn

- How setting state triggers re-renders

- When and how state updates

- Why state does not update immediately after you set it

- How event handlers access a “snapshot” of the state

Setting state triggers renders

You might think of your user interface as changing directly in response to the user event like a click. In React, it works a little differently from this mental model. On the previous page, you saw that setting state requests a re-render from React. This means that for an interface to react to the event, you need to update the state.

In this example, when you press “send”, setIsSent(true) tells React to re-render the UI:

import { useState } from 'react'; export default function Form() { const [isSent, setIsSent] = useState(false); const [message, setMessage] = useState('Hi!'); if (isSent) { return <h1>Your message is on its way!</h1> } return ( <form onSubmit={(e) => { e.preventDefault(); setIsSent(true); sendMessage(message); }}> <textarea placeholder="Message" value={message} onChange={e => setMessage(e.target.value)} /> <button type="submit">Send</button> </form> ); } function sendMessage(message) { // ... }

Here’s what happens when you click the button:

- The

onSubmitevent handler executes. setIsSent(true)setsisSenttotrueand queues a new render.- React re-renders the component according to the new

isSentvalue.

Let’s take a closer look at the relationship between state and rendering.

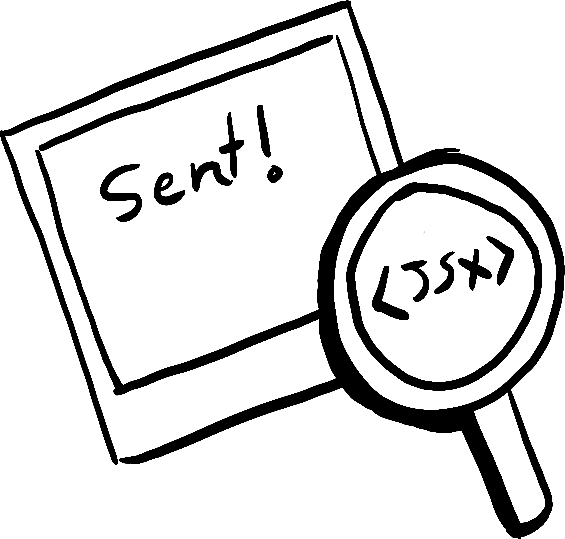

Rendering takes a snapshot in time

“Rendering” means that React is calling your component, which is a function. The JSX you return from that function is like a snapshot of the UI in time. Its props, event handlers, and local variables were all calculated using its state at the time of the render.

Unlike a photograph or a movie frame, the UI “snapshot” you return is interactive. It includes logic like event handlers that specify what happens in response to inputs. React then updates the screen to match this snapshot and connects the event handlers. As a result, pressing a button will trigger the click handler from your JSX.

When React re-renders a component:

- React calls your function again.

- Your function returns a new JSX snapshot.

- React then updates the screen to match the snapshot you’ve returned.

Re-rendering

React executing the function

Calculating the snapshot

Updating the DOM tree

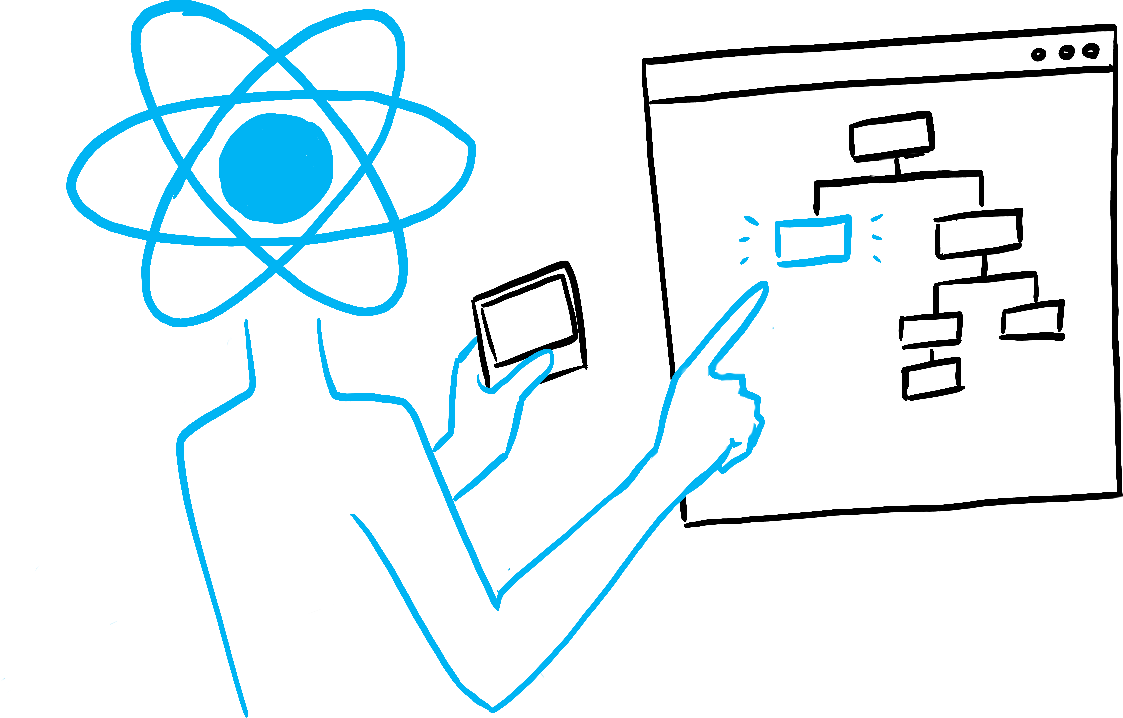

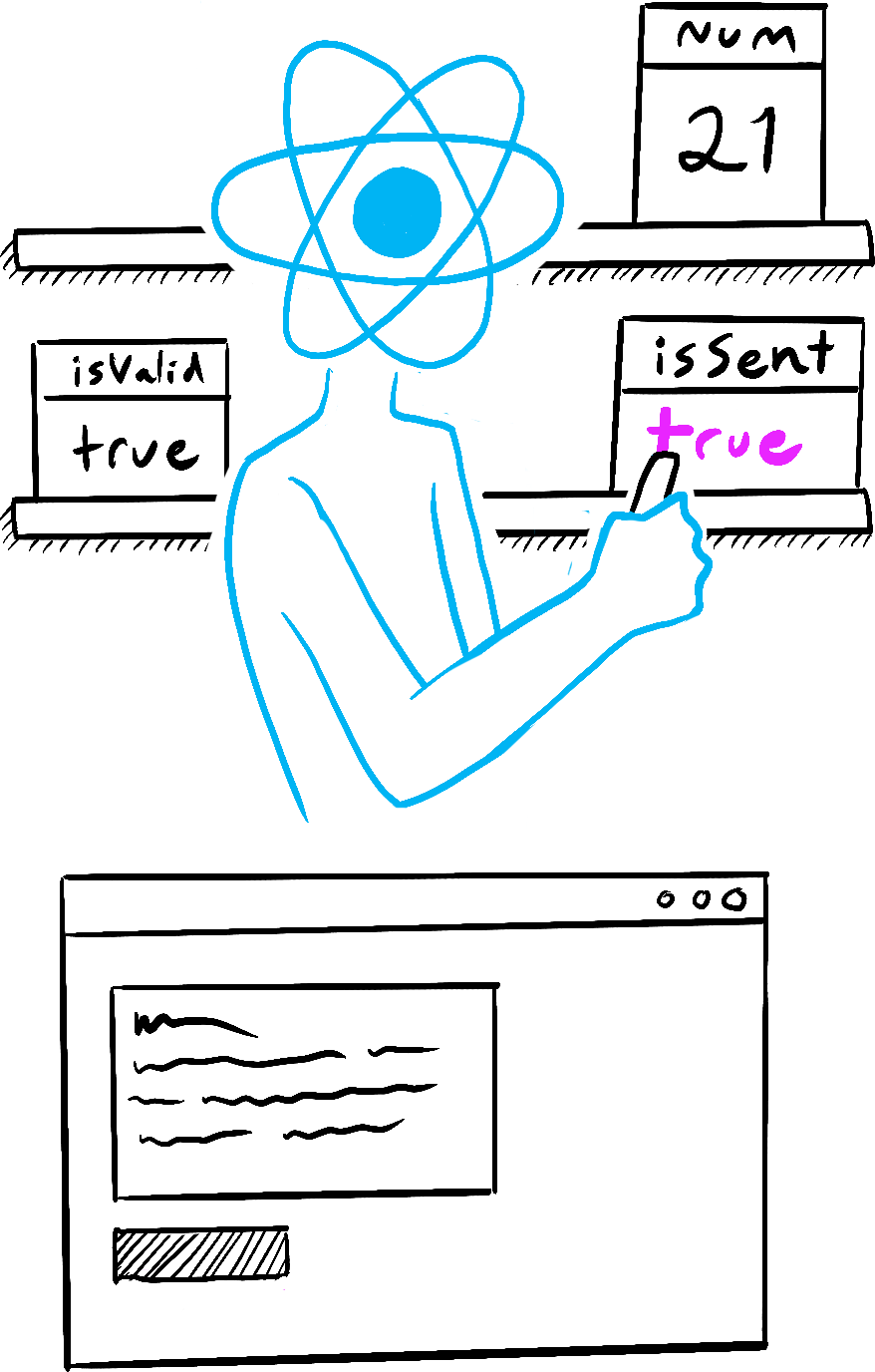

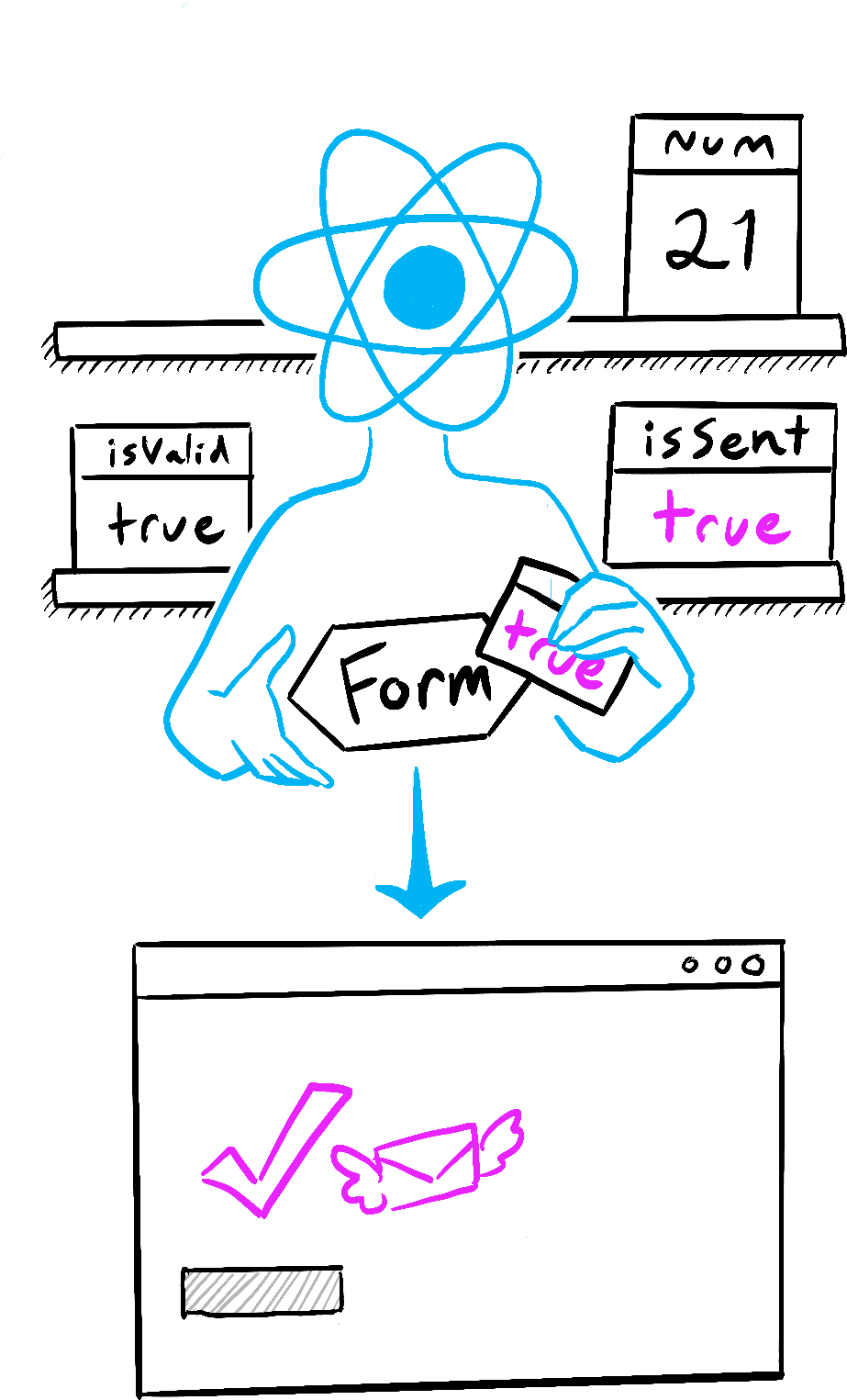

As a component’s memory, state is not like a regular variable that disappears after your function returns. State actually “lives” in React itself—as if on a shelf!—outside of your function. When React calls your component, it gives you a snapshot of the state for that particular render. Your component returns a snapshot of the UI with a fresh set of props and event handlers in its JSX, all calculated using the state values from that render!

You tell React to update the state

React updates the state value

React passes a snapshot of the state value into the component

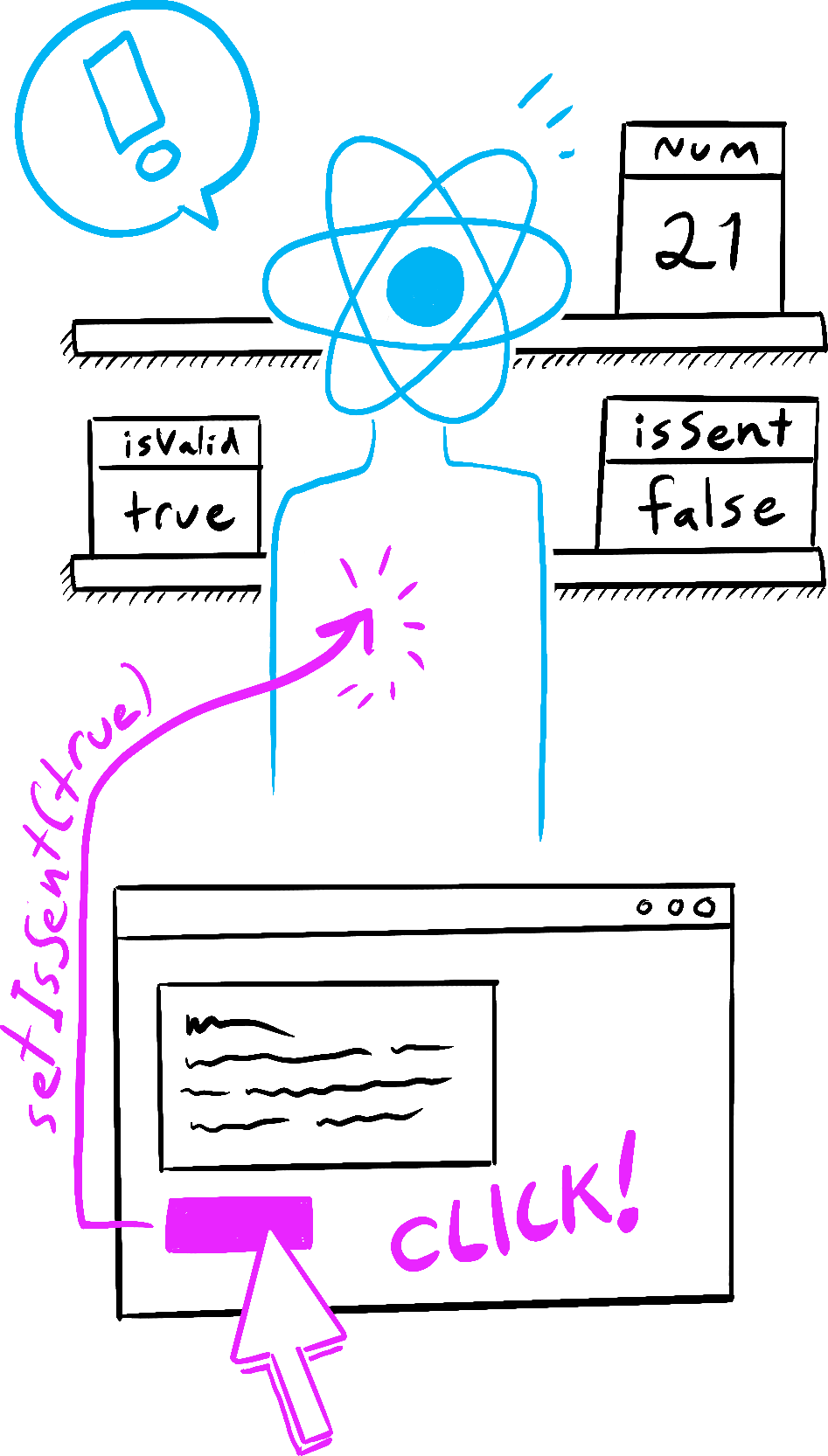

Here’s a little experiment to show you how this works. In this example, you might expect that clicking the “+3” button would increment the counter three times because it calls setNumber(number + 1) three times.

See what happens when you click the “+3” button:

import { useState } from 'react'; export default function Counter() { const [number, setNumber] = useState(0); return ( <> <h1>{number}</h1> <button onClick={() => { setNumber(number + 1); setNumber(number + 1); setNumber(number + 1); }}>+3</button> </> ) }

Notice that number only increments once per click!

Setting state only changes it for the next render. During the first render, number was 0. This is why, in that render’s onClick handler, the value of number is still 0 even after setNumber(number + 1) was called:

<button onClick={() => {

setNumber(number + 1);

setNumber(number + 1);

setNumber(number + 1);

}}>+3</button>Here is what this button’s click handler tells React to do:

setNumber(number + 1):numberis0sosetNumber(0 + 1).- React prepares to change

numberto1on the next render.

- React prepares to change

setNumber(number + 1):numberis0sosetNumber(0 + 1).- React prepares to change

numberto1on the next render.

- React prepares to change

setNumber(number + 1):numberis0sosetNumber(0 + 1).- React prepares to change

numberto1on the next render.

- React prepares to change

Even though you called setNumber(number + 1) three times, in this render’s event handler number is always 0, so you set the state to 1 three times. This is why, after your event handler finishes, React re-renders the component with number equal to 1 rather than 3.

You can also visualize this by mentally substituting state variables with their values in your code. Since the number state variable is 0 for this render, its event handler looks like this:

<button onClick={() => {

setNumber(0 + 1);

setNumber(0 + 1);

setNumber(0 + 1);

}}>+3</button>For the next render, number is 1, so that render’s click handler looks like this:

<button onClick={() => {

setNumber(1 + 1);

setNumber(1 + 1);

setNumber(1 + 1);

}}>+3</button>This is why clicking the button again will set the counter to 2, then to 3 on the next click, and so on.

State over time

Well, that was fun. Try to guess what clicking this button will alert:

import { useState } from 'react'; export default function Counter() { const [number, setNumber] = useState(0); return ( <> <h1>{number}</h1> <button onClick={() => { setNumber(number + 5); alert(number); }}>+5</button> </> ) }

If you use the substitution method from before, you can guess that the alert shows “0”:

setNumber(0 + 5);

alert(0);But what if you put a timer on the alert, so it only fires after the component re-rendered? Would it say “0” or “5”? Have a guess!

import { useState } from 'react'; export default function Counter() { const [number, setNumber] = useState(0); return ( <> <h1>{number}</h1> <button onClick={() => { setNumber(number + 5); setTimeout(() => { alert(number); }, 3000); }}>+5</button> </> ) }

Surprised? If you use the substitution method, you can see the “snapshot” of the state passed to the alert.

setNumber(0 + 5);

setTimeout(() => {

alert(0);

}, 3000);The state stored in React may have changed by the time the alert runs, but it was scheduled using a snapshot of the state at the time the user interacted with it!

A state variable’s value never changes within a render, even if its event handler’s code is asynchronous. Inside that render’s onClick, the value of number continues to be 0 even after setNumber(number + 5) was called. Its value was “fixed” when React “took the snapshot” of the UI by calling your component.

Here is an example of how that makes your event handlers less prone to timing mistakes. Below is a form that sends a message with a five-second delay. Imagine this scenario:

- You press the “Send” button, sending “Hello” to Alice.

- Before the five-second delay ends, you change the value of the “To” field to “Bob”.

What do you expect the alert to display? Would it display, “You said Hello to Alice”? Or would it display, “You said Hello to Bob”? Make a guess based on what you know, and then try it:

import { useState } from 'react'; export default function Form() { const [to, setTo] = useState('Alice'); const [message, setMessage] = useState('Hello'); function handleSubmit(e) { e.preventDefault(); setTimeout(() => { alert(`You said ${message} to ${to}`); }, 5000); } return ( <form onSubmit={handleSubmit}> <label> To:{' '} <select value={to} onChange={e => setTo(e.target.value)}> <option value="Alice">Alice</option> <option value="Bob">Bob</option> </select> </label> <textarea placeholder="Message" value={message} onChange={e => setMessage(e.target.value)} /> <button type="submit">Send</button> </form> ); }

React keeps the state values “fixed” within one render’s event handlers. You don’t need to worry whether the state has changed while the code is running.

But what if you wanted to read the latest state before a re-render? You’ll want to use a state updater function, covered on the next page!

Recap

- Setting state requests a new render.

- React stores state outside of your component, as if on a shelf.

- When you call

useState, React gives you a snapshot of the state for that render. - Variables and event handlers don’t “survive” re-renders. Every render has its own event handlers.

- Every render (and functions inside it) will always “see” the snapshot of the state that React gave to that render.

- You can mentally substitute state in event handlers, similarly to how you think about the rendered JSX.

- Event handlers created in the past have the state values from the render in which they were created.

Challenge 1 of 1: Implement a traffic light

Here is a crosswalk light component that toggles on when the button is pressed:

import { useState } from 'react'; export default function TrafficLight() { const [walk, setWalk] = useState(true); function handleClick() { setWalk(!walk); } return ( <> <button onClick={handleClick}> Change to {walk ? 'Stop' : 'Walk'} </button> <h1 style={{ color: walk ? 'darkgreen' : 'darkred' }}> {walk ? 'Walk' : 'Stop'} </h1> </> ); }

Add an alert to the click handler. When the light is green and says “Walk”, clicking the button should say “Stop is next”. When the light is red and says “Stop”, clicking the button should say “Walk is next”.

Does it make a difference whether you put the alert before or after the setWalk call?